Despite steady capital investment and economic growth following the 2008 financial crisis and housing bubble, a shortfall of new residential housing construction remains.[5] This shortage—along with the consequent rise in housing prices—is felt most acutely by lower-income workers in search of affordable housing.

In fact, a 2019 Harvard University study concluded that over 75 percent of households making under $30,000 are moderately or severely “housing cost burdened,” meaning over 30 percent of their income goes toward housing costs.[6] The study concluded that available housing supply is usually built and marketed to higher-income earners above the median income.[7]

The shortage of attractive and affordable housing has been a chronic problem in the United States at least since the beginning of the post-war period. As part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, policymakers created the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit A tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. (LIHTC) to address the mismatch between housing supply and demand by encouraging developers to build units specifically allocated for residents with incomes below their area median income (AMI).

Since it was created, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit has subsidized over 47,500 projects and 3.13 million housing units, using an average of $8 billion in forgone revenue to subsidize the costs of building more than 107,000 units across 1,411 projects each year.[8] Today, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit is the largest source of affordable housing financing in the United States.[9]

The LIHTC offers developers nonrefundable and transferable tax credits to subsidize the construction and rehabilitation of housing developments with strict income limits on eligible tenants and their cost of housing.[10] The LIHTC may be claimed annually over the course of 10 years once the constructed units are put in service (i.e., available for occupancy).[11] Additionally, developers can sell their credits to investors in exchange for project funding.[12]

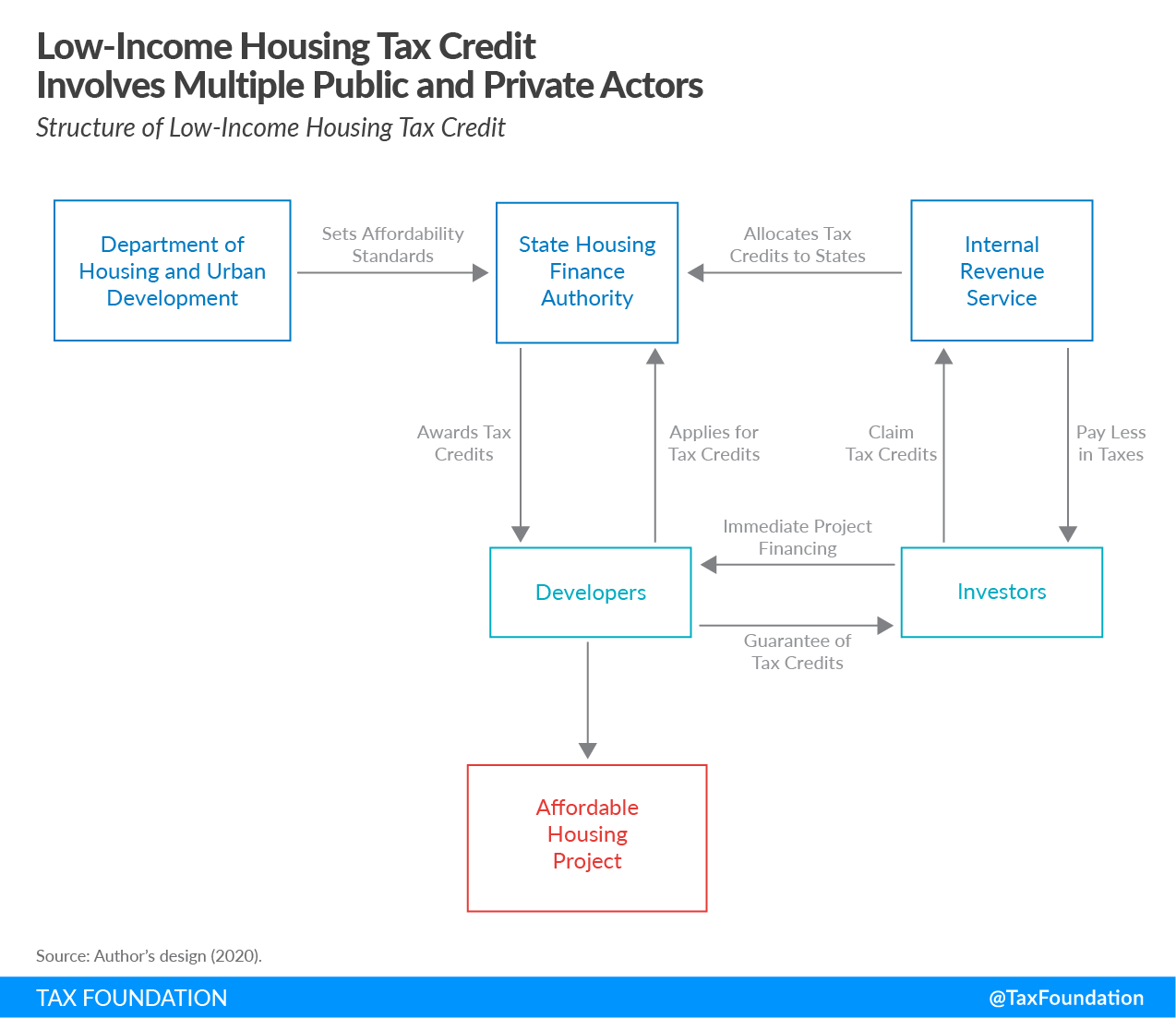

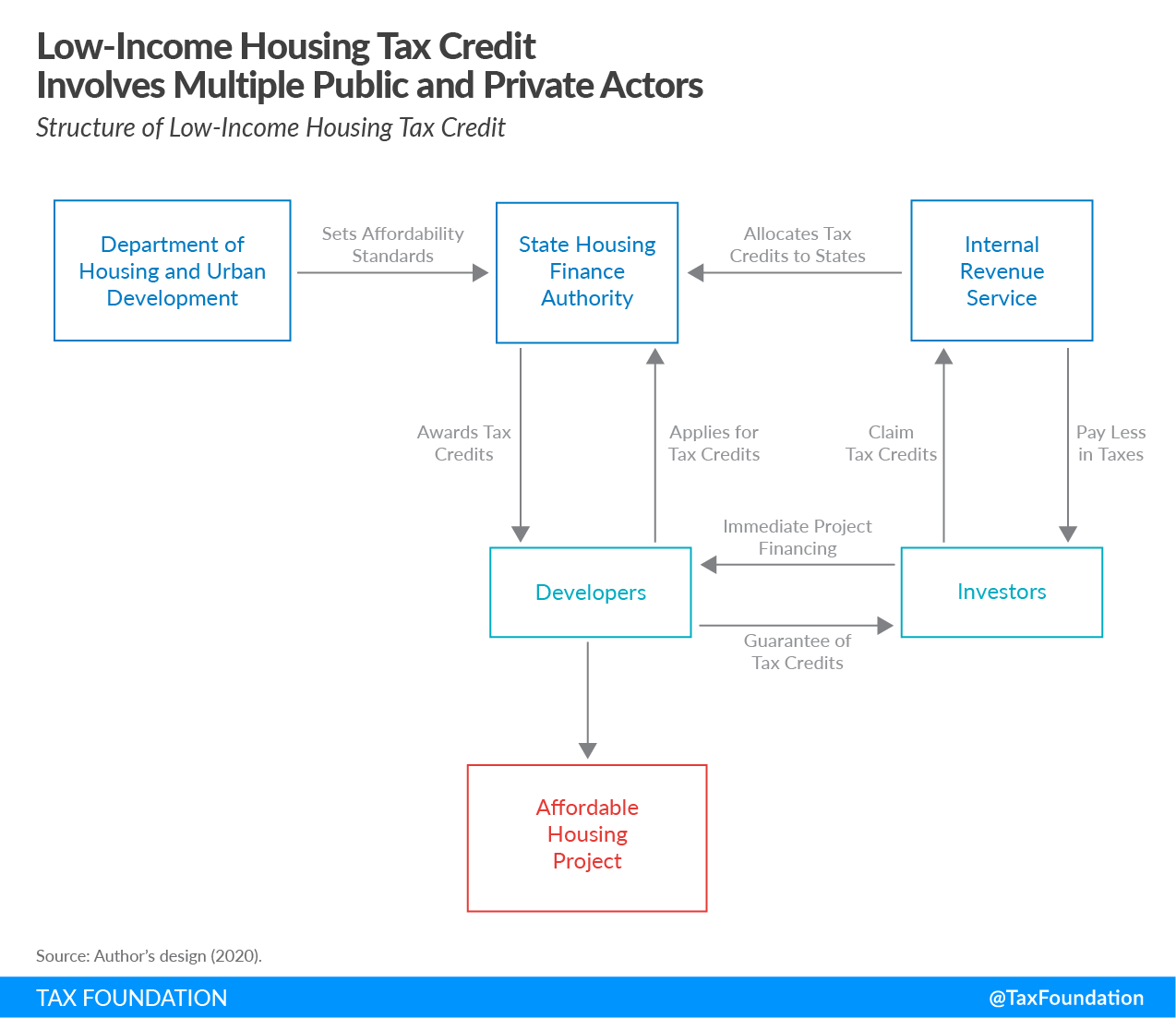

The credits are allocated from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to Housing Finance Authorities (HFAs) at the state level, which use the minimum affordability requirements detailed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to create their own guidelines (Figure 1).[13]

A typical project involves several private and public actors from initial regulation to finished residential property (see Figure 1):

Changes proposed in the Tax Reform Act of 1986 regarding the tax treatment of real estate and structures, particularly rental housing, sounded alarms for low-income housing advocates.[16] The Tax Reform Act increased the depreciation period of residential and nonresidential real property from 19 years to 27.5 years and 31.5 years respectively, and limited deductions of passive investment losses.[17] Both changes would reduce the benefits the tax code provided to rental housing investment.[18]

In response, affordable housing advocates partnered with the construction industry and successfully lobbied for the inclusion of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit within the Tax Reform Act, hoping to offset the Act’s other impacts on rental housing.[19] Due to a sunset provision, the credit was initially set to expire after three years if Congress took no action to extend the credit.[20]

After repeated extensions and improvements to the credit’s structure, the LIHTC was made permanent in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993.[21] At that time, LIHTC developments made up 25 percent of all new multifamily residential construction and “virtually all” housing for households with incomes under $15,000.[22] It also enjoyed bipartisan support in Congress.[23]

Since LIHTC allocations and transfers rely on initial private investment to construct the units where the credit will be applied, the credit’s impact and cost fluctuate with the economy. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) calculated that—on average—LIHTC costs about $9.9 billion annually.[24] Before the TCJA, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that LIHTC transfers constituted $8.4 billion in forgone revenue in 2017.[25] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that repealing the credit would increase federal revenues by $49.4 billion between 2019 and 2028.[26]

Despite its dependence on private investment and annual (along with cyclical) fluctuations, the credit remained a critical part of affordable residential construction projects and weathered high rental vacancy rates in the late 1980s, rent deflation in the early 1990s, and the 2001 recession A recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. .[27]

The 2007-08 subprime mortgage crisis and the subsequent recession led to reduced income for corporations, decreasing the need for many firms to offset their taxable income with nonrefundable credits. As a result, there was a sharp decrease in affordable residential construction and applications for the LIHTC.[28]

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the largest government-sponsored mortgage financers (GSEs) that previously constituted approximately 40 percent of LIHTC investment, withdrew from the LIHTC market in 2008 as their projected losses from the recession would offset their taxable income Taxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. for the foreseeable future.[29] Fannie and Freddie were subsequently placed under conservatorship, whereby the Treasury Department and the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) managed both entities until they could be recapitalized. The reduction in investor participation by Fannie and Freddie caused significant funding gaps in many LIHTC projects nationwide.[30]

To ameliorate the downturn in investment, Congress enacted two programs as part of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). First, the Tax Credit Assistance Program provided federal grants to assist LIHTC projects struggling to find investors. Second, the Tax Credit Exchange Program allowed state HFAs to exchange unused tax credits for funding through Treasury at a rate of 85 cents per dollar. This funding was to be awarded to LIHTC projects where investors had backed out.[31] Both programs were available to LIHTC projects initiated between 2007 and 2009.

In the 2010s, as the rest of the economy recovered, so did the LIHTC market. With the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017, the corporate tax rate was reduced from 35 percent to 21 percent. Since corporations owed less in corporate income tax each year, there was concern that the need for tax credits would fall, reducing investment for LIHTC-financed projects.

The 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act increased the amount of tax credits available by 12.5 percent in all states through 2021 and added new affordability guidelines.[32] The increase in tax credits allowed for more affordable housing units to be financed through LIHTC.

LIHTC’s minimum affordability requirements detail the rental rate at which a unit can be offered to be considered “affordable,” who can qualify for affordable housing, and what percentage of a project’s units must be affordable to qualify for the credit. The first requirement is commonly used in HUD programs: a unit is affordable if the tenant is spending 30 percent or less of their monthly adjusted gross income (AGI)[33] on housing costs (i.e., rent plus utilities).[34] Additionally, using HUD’s Area Median Income (AMI) measurements, a project must provide either 20 percent of units at an affordable rate for tenants at or below 50 percent of AMI or 40 percent of units at an affordable rate for tenants at or below 60 percent of AMI.[35] The second and third requirements are evaluated together and can be satisfied in several ways.

Additionally, the 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act reformed LIHTC by allowing an additional affordability metric: a household earning up to 80 percent of AMI can qualify for an affordable unit if the average income of all subsidized units is below 60 percent of AMI.[36] This change was made to prevent clustering of incomes around the upper AMI limit. Currently, projects can house tenants from lower income levels without losing revenue, as they can now be subsidized by higher-income tenants.

These affordability criteria must be maintained for 30 years, enforced by owners reporting their compliance to the IRS and their state HFA. Enforcement is backed by the potential for the IRS to reclaim the tax credits. The first 15 years are known as the “initial compliance period.” The last 15 years are called the “extended use period.” The extended use period brings about several changes to compliance. While owners are still required to maintain affordability during the extended use period, they are no longer obliged to report affordability compliance to the IRS and their state HFA and are no longer at risk of having their tax credits reclaimed.[37]

The LIHTC is composed of two major credit types: the 4 percent credit and 9 percent credit. Credits are redeemable every year for 10 years and calculated as 4 percent or 9 percent of the project’s qualified basis, a figure calculated from the gross construction costs of the project’s affordable units.

Both credits provide housing tied to the same affordability requirements.[38] The 4 percent credit is awarded non-competitively through the federal government and does not impact a state HFA’s annual allocation. In other words, all projects that meet the 4 percent criteria will receive the credit. The 4 percent credit is for projects already receiving most of their funding through tax-exempt bonds or other government subsidies and the acquisition, rehabilitation, and conversion of existing structures to affordable housing.

The 9 percent credit is awarded through a competitive allocation process by state HFAs. States develop a Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP), which details the minimum requirements for credit eligibility as well as scoring criteria to compare project applications. The specific criteria of each state are unique. However, there are several general goals that a majority of HFAs seek to incentivize, such as number of affordable units, project cost thresholds, and quality of housing.[39]

Importantly, project applicants either receive the 4 percent credit or the 9 percent credit, but not both. While applicants may submit multiple applications for different projects which qualify for each credit respectively, an applicant may not qualify for a 4 percent credit and a 9 percent credit on the same project.

Interestingly, the 4 percent and 9 percent credits rarely end up being precisely 4 and 9 percent each year but a 10-year stream of credits equal to 30 percent and 70 percent of the qualified basis. As interest rates fluctuate with the economy, the yearly value of the tax credits fluctuates around 4 percent and 9 percent. The final value of the 4 percent and 9 percent credits are called the Appropriate Percentages[40] and are set by the IRS.[41]

To illustrate how these calculations interact, Mark Keightley and Jeffrey Stupak at the Congressional Research Service (CRS) provide an example in their background primer on the LIHTC:

A simplified example may help in understanding how the LIHTC program is intended to support affordable housing development. Consider a new apartment complex with a qualified basis of $1 million. Since the project involves new construction it will qualify for the 9 [percent] credit and, assuming for the purposes of this example that the credit rate is exactly 9 [percent], will generate a stream of tax credits equal to $90,000 (9 [percent] × $1 million) per year for 10 years, or $900,000 in total. Under the appropriate interest rate the present value of the $900,000 stream of tax credits should be equal to $700,000, resulting in a 70 [percent] subsidy.[42]

Indeed, calling them the “4 percent credit” and “9 percent credit” is a naming convention and not the realized value of the tax credits. In 2015, several years of low interest rates resulted in several years of the “4 percent” and “9 percent” credits realizing values significantly below 4 percent and 9 percent. In response, Congress passed the PATH Act and set a permanent floor for the 9 percent credit, declaring that regardless of the current interest rate, the 9 percent credit would be worth a minimum of 9 percent each year.[43] This did not apply to the 4 percent credit.[44]

While the official minimum criteria allow for a low of 20 percent of units to be affordable, it is common for projects to promise 100 percent affordable units to ensure their application is competitive and they can receive the maximum amount of tax credits .[45] Between 1986 and 2018, approximately 70 percent of projects offered 100 percent affordable units.[46] Additionally, some QAPs seek to incentivize broader social goals such as a project’s environmental impact, proximity to public transit, and occupancy preferences (for the elderly, families, special needs, etc.).[47]

For example, the 2020 Arizona Qualified Allocation Plan included criteria “to make tax credit funding available to projects serving low-income populations – including families with children, homeless persons, veterans, and older person citizens, to develop and promote energy and water efficient housing, to develop rental housing in locations that are within reasonable proximity to frequent bus transit or to high capacity transit,” among other goals.[48]

In 2020, state HFAs will receive the greater of $2.81 per capita or minimum small population state allocation of $3,217,500 to award to 9 percent projects. The minimum small population state allocation was originally $2 million but has been indexed to inflation since 2004.[49] These amounts include the temporary 12.5 percent increase in funding passed in the 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act.[50] This allocation does not apply to 4 percent credits.

Developers apply to state HFAs with their proposed projects and tax credits are allocated according to how well they meet the criteria of their state’s QAP. The tax credits are not redeemable until the project is finished and placed in service. As a result, developers typically enter contracts with investors who provide immediate project financing in exchange for the anticipated claimed tax credits. Often, these deals are facilitated by “syndicators,” who specialize in matching developers to investors for a fee.

Investors require return on their investment, so credits are typically purchased from developers at a discount. Since the passage of the TCJA, the value of $1 in tax credits has fluctuated between $0.90 and $0.95,[51] meaning investors can expect to trade $1 in tax credits to investors for $0.90-$0.95 in immediate project financing.

Additionally, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) encourages banks to provide financing to members of their local communities. LIHTC investment is one such favorable form of financing. Specifically, investing in LIHTC developments is interpreted under the CRA as “community development” and viewed positively by regulators who score banks on CRA compliance.[52]

Despite the program’s bipartisan support and status as the largest source of affordable housing financing in the United States, it is not without fault. Researchers have found problems with how effective the program is at directing subsidies to low-income tenants. Michael Eriksen’s 2009 paper in the Journal of Urban Economics found that LIHTC developers produce “housing units that are an estimated 20 [percent] more expensive per square foot than average industry estimates.”[53] Eriksen explains that the higher cost results from having either “superior quality” or “far less efficient” production than those produced without LIHTC funding.[54] This is consistent with a 2001 GAO report that found LIHTC developments cost 16 [percent] more than voucher programs that provided similar subsidies to low-income households.[55]

More recently, a 2020 paper by the Arizona Free Enterprise Club found that the construction costs per square foot were significantly higher in LIHTC developments than equivalent market rate developments. The study found increases of $39.87 and $77.82 per square foot in the states of Arizona and Washington, respectively.[56]

There are also concerns about oversight and accountability within the credit’s administration. According to a 2017 GAO report on the LIHTC, only 68 percent of allocating agencies had limits on development costs and only 60 percent had limits on credit allocations per unit, per project, or per developer.[57] The GAO also reported that the lack of oversight on contractor costs means “the vulnerability of the LIHTC program to fraud risk is heightened.”[58]

A paper from the Cato Institute released the same year reveals the heightened risk mentioned by the GAO was well-founded, listing multiple cases of fraud in the LIHTC program. This is enabled by the opaque and discretionary LIHTC allocation process, where projects are awarded to developers who inflate or fabricate contractor fees, thus increasing the LIHTC award they receive from the government. These fraudulent fees are paid to shell companies where contractors are the direct beneficiaries. Often, government officials overseeing LIHTC allocation decisions have received campaign contributions[59] from these contractors or a kickback from the money from the fraudulent payments.[60] The Cato Institute paper lists examples where a settlement or conviction occurred, including two from Miami, one from Norman, Oklahoma, one from Los Angeles, and one from Dallas, each amounting to millions of dollars in fraud or misallocated funds.[61]

Recently, former LIHTC administrator Jason Vrabel wrote about the “difficulties of the process, design challenges, construction delays, and need to meet strict deadlines set by the LIHTC program.”[62]According to his own estimation, the attempt to produce LIHTC housing units in Pittsburgh was successful, but not without great cost. Vrabel concluded that the attempt “showed how much coordination and funding is needed to make affordable housing work.”[63]

Administrative improvements at the state level could be made to reduce the potential occurrence of fraud; however, those also come at a cost. For example, California spent $9.6 million on the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee for 2019, with the sole purpose to administer the LIHTC program.[64]

LIHTC was motivated in part due to the threat posed to affordable housing programs by the Tax Reform Act of 1986’s extension of depreciation Depreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. periods for real property.[65] Long depreciation lives remain an impediment to affordable housing development in the United States. Moving towards neutral cost recovery for residential structures can make affordable housing developments more cost-effective.[66]

Overall, this suggests that the LIHTC program is an inefficient and unwieldy mechanism for providing affordable housing. Despite averaging an annual $9.9 billion in tax expenditures, there is extensive evidence to suggest that only a fraction of this translates into housing units for eligible low-income tenants. Instead, a significant portion of federal funding benefits developers and investors or is wasted on bureaucratic complexity, high construction costs, and fraud. Oversight of the program is largely ad hoc, reactionary, and reflective rather than standardized, anticipatory, and proactive.

The dwindling supply of affordable housing might suggest the need for more LIHTC projects; however, the program’s issues must first be addressed for it to function well. Additionally, other policy changes such as improved cost recovery Cost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker ’s productivity and wages. could be explored as solutions to the lack of affordable housing. As outlined in the GAO report, improved record keeping, data sharing, and oversight would strengthen cost assessment and fraud risk management in the LIHTC program.[67]

Created in 1986, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) is an exceptionally complex tax expenditure Tax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. that now represents the largest source of affordable housing financing in the United States. From credit allocation to compliance assessment, numerous public and private entities play a role in constructing affordable housing.

Congress allocates credit amounts for each state while the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and State Housing Finance Authorities (HFAs) craft affordability requirements and standards of quality for projects. Local developers respond by planning projects relative to credit availability. Many credit applicants finance the start of construction by trading their current and anticipated tax credits for immediate funding from outside investors, who ultimately redeem the tax credits and reduce their tax liability with the IRS.

While the goal of the credit is to provide high-quality, affordable rental housing to low-income households, the evidence suggests the credit is not effective in achieving this goal. Despite its apparent ineffectiveness, the credit has maintained participation from local developers and continued extensions from a bipartisan coalition of Congressional lawmakers.

As the supply of affordable rental housing for lower-income households continues to decline, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit will remain at the forefront of the housing policy debate.[68]

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

[1]Will Fischer, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Could Do More to Expand Opportunity for Poor Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Aug. 28, 2018, 1, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/8-28-18hous.pdf.

[2]Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credits,” June 5, 2020, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/lihtc.html.

[3] Michael Eriksen, “The Market Price of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits,” Journal of Urban Economics 66:2 (September 2009), 141–49.

[4] Daniel Garcia-Diaz, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: Improved Data and Oversight Would Strengthen Cost Assessment and Fraud Risk Management,” Government Accountability Office, September 2018, 1, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/694541.pdf.

[5] Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, “The State of the Nation’s Housing: 2019,” https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_State_of_the_Nations_Housing_2019.pdf.

[8] Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credits.”

[9] Fischer, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Could Do More to Expand Opportunity for Poor Families,” 1.

[10] Tax credits reduce tax liability dollar-for-dollar. Nonrefundable credits can only reduce tax liability until it reaches $0. By contrast, refundable credits may result in a refund for the filer if the credit amount is greater than their total liability.

[11] Mark P. Keightley, “An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” Congressional Research Service, Feb. 27, 2019, 2, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RS22389.pdf.

[12] Tax Policy Center, “What Is the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit and How Does It Work?” May 2020, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-low-income-housing-tax-credit-and-how-does-it-work.

[13] Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, “26 U.S.C. 42. Low-Income Housing Credit,” July 2020, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/42.

[14] Keightley, “Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” 2.

[15] Connecticut Housing Finance Authority, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Compliance Manual,” May 2019, 48, https://spectrumlihtc.com/wp-content/uploads/CT-LIHTC-Compliance-Manual-2019.pdf.

[16] Kirk McClure, “The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit as an Aid to Housing Finance: How Well Has It Worked?,” Housing Policy Debate 11:1 (2000): 94–95, https://www.innovations.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/hpd_1101_mcclure.pdf.

[17] Roy E. Cordato, “Destroying Real Estate through the Tax Code. (Tax Reform Act of 1986),” The CPA Journal Online (June 1991), http://crab.rutgers.edu/~mchugh/taxes/Destroying%20real%20estate%20through%20the%20tax%20code_%20%28Tax%20Reform%20Act%20of%201986%29.htm.

[19] Karl E. Case, “Investors, Developers, and Supply‐side Subsidies: How Much Is Enough?,” Housing Policy Debate 2:2 (1991), 350, https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080%2F10511482.1991.9521055.

[20] McClure, “The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit as an Aid to Housing Finance: How Well Has It Worked?,” 95.

[21] Martin Olav Sabo, “H.R. 2264 – Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, https://www.congress.gov/bill/103rd-congress/house-bill/2264?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22cite%3APL103-66%22%5D%7D&r=1.

[22] U.S. Senate, “Concurrent Resolution on the Budget for Fiscal Year 1993: Hearings Before the Committee on the Budget, United States Senate, One Hundred Second Congress, Second Session, Volume 1,” Dec. 31, 1992, 291, https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=R18UZnMx_eQC.

[23] Affordable Rental Housing A.C.T.I.O.N., “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” Spring 2013, 3, http://static1.squarespace.com/static/566ee654bfe8736211c559eb/t/56b8ae57356fb0ff251b42e2/1454943831407/LIHTC_ACTION_FINAL2.2.pdf.

[24] Computed as the average estimated tax expenditure associated with the program between 2018 and 2022. See Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” Oct. 4, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=fileinfo&id=5149.

[25] Garcia-Diaz, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: Improved Data and Oversight Would Strengthen Cost Assessment and Fraud Risk Management,” 1.

[26] Congressional Budget Office, “Repeal the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” Dec. 13, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/2018/54814.

[27] Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, “The Disruption of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program: Causes, Consequences, Responses, and Proposed Correctives,” December 2009, 22, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/disruption_of_the_lihtc_program_2009_0.pdf..

[28] Heidi Kaplan and Matt Lambert, “Innovative Ideas for Revitalizing the LIHTC Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2009, 4, https://www.federalreserve.gov/other20091110a1.pdf.

[29] Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, “The Disruption of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program: Causes, Consequences, Responses, and Proposed Correctives,” 5.

[31] Michael A. Anderson, “Tax Credit Exchange Program (TCEP) Implementation Process,” North Dakota Housing Finance Agency, Oct. 30, 2009, 1, https://www.novoco.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/ok_exchangeprocess.pdf.

[32] Rep. Edward R. Royce, “H.R. 1625, – Consolidated Appropriations

Act, 2018,” 811, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1625?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22cite%3APL115-141%22%5D%7D&s=1&r=1.

[33] Adjusted Gross Income For individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” is gross income minus certain deductions a tenant may qualify for. Major deductions include a deduction for dependents, childcare deduction, disability assistance deduction, elderly/disabled family deduction, and unreimbursed medical expense deduction. See Chapter 5, “Determining Income and Calculating Rent,” in U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD Occupancy Handbook (Washington, DC: HUD), 2007.

[35] Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, “26 U.S. Code § 42. Low-Income Housing Credit.”

[37] U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “What Happens to LIHTC Properties After Affordability Requirements Expire?,” n.d., https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr_edge_research_081712.html.

[38] Keightley, “Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” 2.

[39] Corianne Payton Scally, Amanda Gold, and Nicole DuBois, “The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit How It Works and Who It Serves,” Urban Institute, July 2018, 4, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98758/lithc_how_it_works_and_who_it_serves_final_2.pdf.

[40] The Appropriate Percentages are calculated using a discount rate equal to 72 percent of the average of the federal mid-term and long-term Applicable Federal Rates. Using that discount rate, the 30 percent or 70 percent of the qualified basis is disbursed in tax credits as a 10-year annuity due. Source: I.R.C. § 42(b)(1).

[41] National Housing and Rehabilitation Association, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Rates,” n.d., https://www.housingonline.com/resources/facts-figures/low-income-housing-tax-credit-rates/.

[42] Keightley, “Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” 3.

[43] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Technical Explanation of The Protecting Americans From Tax Hikes Act Of 2015,” Dec.17, 2015, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4861.

[44] Mark P. Keightley and Jeffery M. Stupak, “The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program: The Fixed Subsidy and Variable Rate,” Congressional Research Service, July 16, 2015, 2, https://www.novoco.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/crs_lihtc-fixed-subsidy-variable-rate_071615.pdf.

[46] Author calculations, from Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credits.”

[48] Arizona Department of Housing, “Arizona 2020 Qualified Allocation Plan for the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program” Jan. 18, 2019, 26, https://www.novoco.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/arizona_2020_qap_121819.pdf.

[49] Keightley, “Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” 2.

[50] Royce, “H.R. 1625, – Consolidated Appropriations

Act, 2018,” 811.

[51] Novogradac, “LIHTC Pricing Trends, January 2016-May 2020,” n.d., https://www.novoco.com/resource-centers/affordable-housing-tax-credits/data-tools/lihtc-pricing-trends.

[52] David Erickson, “CRA Investment Handbook,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, March 2010, 11, https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/CRAHandbook.pdf.

[53] Eriksen, “The Market Price of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits,” 141.

[55] Stanley J. Czerwinski, “Federal Housing Programs: What They Cost and What They Provide,” United States Government Accountability Office, July 18, 2001, 3, https://www.gao.gov/assets/100/90783.pdf.

[56] Everett Stamm, “Analysis of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program,” Arizona Free Enterprise Club, Jan. 31, 2020, https://www.azfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/LowIncomeHousing_PolicyPaper.pdf.

[57] Garcia-Diaz, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: Improved Data and Oversight Would Strengthen Cost Assessment and Fraud Risk Management,” 176.

[59] Christian Britschgi, “California Gubernatorial Candidate Steered Low-Income Housing Funds To Campaign Contributors,” Reason, Aug. 15, 2017, https://reason.com/2017/08/15/influence-peddling-scandal-wracks-feds-l/.

[60] The Dallas Morning News, “Jibreel Rashad Found Guilty in Dallas City Hall Corruption Trial,” Feb. 11, 2010, https://www.dallasnews.com/news/crime/2010/02/11/jibreel-rashad-found-guilty-in-dallas-city-hall-corruption-trial/.

[61] Chris Edwards and Vanessa Brown Calder, “Low‐Income Housing Tax Credit: Costly, Complex, and Corruption‐Prone,” Cato Institute, Tax and Budget Bulletin, no. 79, Nov. 13, 2017, https://www.cato.org/publications/tax-budget-bulletin/low-income-housing-tax-credit-costly-complex-corruption-prone.

[62] Jason Vrabel, “Developing Affordable Housing Isn’t Easy. The Story of This Oakland Complex Shows What It Takes.,” Public Source, Jan. 6, 2020, https://www.publicsource.org/developing-affordable-housing-isnt-easy-the-story-of-this-oakland-complex-shows-what-it-takes/.

[64] Gov. Gavin Newsom, “California State Budget 2019-20, Section 0968: California Tax Credit Allocation Committee,” California State Treasurer, June 2019, 1, http://www.ebudget.ca.gov/2019-20/pdf/Enacted/GovernorsBudget/0010/0968.pdf.

[65] Alex Muresianu, “Did 1986 Tax Reform Hurt Affordable Housing?,” July 1, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/1986-tax-reform-hurt-affordable-housing/.

[66] Scott A. Hodge, “Improving the Tax Treatment of Residential Buildings Will Stretch Affordable Housing Assistance Dollars Further,” Tax Foundation, June 25, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/improving-the-tax-treatment-of-residential-buildings-stretch-affordable-housing-assistance-dollars-further/.

[67] Garcia-Diaz, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: Improved Data and Oversight Would Strengthen Cost Assessment and Fraud Risk Management,” 1.

[68] Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, “State of the Nation’s Housing, 2019,” 29–30.